Politics

UNANIMOUS FRENCH ASSEMBLY VOTE OPENS PARLIAMENTARY INQUIRY INTO PARENTAL INCEST

160 000/YEAR CHILDREN ABUSED IN FRANCE

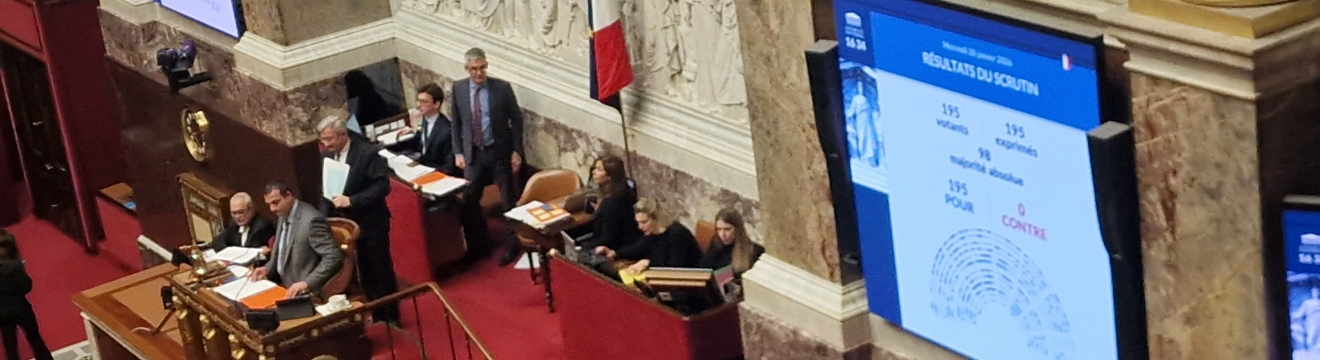

French National Assembly Voting Incest Bill (Source: Rahma Sophia Rachdi, Jedi Foster)

USPA NEWS -

In a rare moment of complete cross party unity, the French National Assembly voted by 195 votes to none on 28 January to create a commission of inquiry into the judicial treatment of parental incestuous sexual violence and the situation of so called “protective parents,” most often mothers who try to shield their children from an abusive father. The resolution, tabled by Christian Baptiste, Socialist affiliated deputy from Guadeloupe and rapporteur for the Law Committee, had already been co signed by more than 140 MPs from almost every group, signalling broad support well before the text reached the floor. Behind the technical title of the new body a “commission of inquiry into the judicial treatment of parental incestuous sexual violence committed against children and the situation of protective parents, in particular protective mothers” lies a stark assessment shared across the hemicycle: the French justice system is failing to protect thousands of children trapped in abusive families, and is sometimes punishing the very parent who dares to denounce the abuse.

160, 000 CHILDREN ABUSED IN FRANCE EACH YEAR

Throughout the debate, deputies returned again and again to the same set of figures: an estimated 160,000 children in France are victims of rape or sexual assault each year, and roughly 77% of these acts are committed within the family, most often by fathers or stepfathers. These numbers, consolidated by the independent commission on incest and sexual violence against children (Ciivise), imply that virtually every adult in France knows, often without realising it, at least one person whose life has been shattered by incest. Yet only a small fraction of accused parents are ever convicted, and a significant share of complaints are closed without further action, sometimes despite medical certificates, school reports or digital evidence. For Baptiste and his colleagues, this discrepancy points not to isolated errors but to structural failings a justice system split between criminal, family and child protection courts that do not always share information, and that move too slowly to protect a child still compelled to see an alleged aggressor under visitation rights that remain in force.

Throughout the debate, deputies returned again and again to the same set of figures: an estimated 160,000 children in France are victims of rape or sexual assault each year, and roughly 77% of these acts are committed within the family, most often by fathers or stepfathers. These numbers, consolidated by the independent commission on incest and sexual violence against children (Ciivise), imply that virtually every adult in France knows, often without realising it, at least one person whose life has been shattered by incest. Yet only a small fraction of accused parents are ever convicted, and a significant share of complaints are closed without further action, sometimes despite medical certificates, school reports or digital evidence. For Baptiste and his colleagues, this discrepancy points not to isolated errors but to structural failings a justice system split between criminal, family and child protection courts that do not always share information, and that move too slowly to protect a child still compelled to see an alleged aggressor under visitation rights that remain in force.

The new commission of inquiry is designed to complement, not replace, judicial work by using the tools specific to Parliament: hearings under oath, document reviews and the power to evaluate public policies as a whole. Its mandate is to examine why so many complaints are closed without investigation, why civil courts sometimes maintain contact with a parent under criminal suspicion, how the child’s testimony is collected and interpreted, and in what conditions protective parents end up prosecuted for non presentation of a child when they refuse to comply with orders they consider dangerous. Several speakers also linked these dysfunctions to chronic under funding of the justice system: insufficient numbers of magistrates and specialised investigators, overloaded courts, lack of child friendly interview facilities and too few professionals trained in trauma and child psychology. In their view, delays and gaps are not only the product of legal culture or patriarchal reflexes, but also of a shortage of financial and human resources that leaves prosecutors and judges unable to pursue every case with the rigour required.

A CHAMBER'S COMMITTEE VOTED TO ACCELERATE & COMPLETE THE JUSTICE PROCESS

The commission’s creation thus sends a double message. To victims and protective parents, deputies wanted to say that their experiences are finally being recognised at the highest institutional level, and that Parliament will use its oversight powers to force the system to look itself in the mirror. To the government and judicial authorities, the unanimous 195–0 vote is a warning that the current pace and severity of responses to parental incest are no longer politically acceptable, and that legislative and budgetary follow up will be expected once the commission delivers its report. For a country where debates on crime and justice are often polarised, the sight of MPs from the left, centre, right and far right applauding each other’s interventions and one Ecologist deputy moved to tears underlined how deeply the issue of protecting children cuts across partisan lines.

The commission’s creation thus sends a double message. To victims and protective parents, deputies wanted to say that their experiences are finally being recognised at the highest institutional level, and that Parliament will use its oversight powers to force the system to look itself in the mirror. To the government and judicial authorities, the unanimous 195–0 vote is a warning that the current pace and severity of responses to parental incest are no longer politically acceptable, and that legislative and budgetary follow up will be expected once the commission delivers its report. For a country where debates on crime and justice are often polarised, the sight of MPs from the left, centre, right and far right applauding each other’s interventions and one Ecologist deputy moved to tears underlined how deeply the issue of protecting children cuts across partisan lines.

KEY FIGURES BEHIND THE INQUIRY COMMISSION

The debate was chaired by Christophe Blanchet, vice president of the National Assembly, who presided over the sitting and coordinated the speaking time of all groups. The driving force behind the text was Christian Baptiste, Socialist affiliated deputy for Guadeloupe and rapporteur for the Law Committee, who authored the resolution, presented the statistical scale of incest (160,000 child victims per year, 77% within the family) and framed the commission as a way to expose systemic judicial failures and protect “protective parents,” especially mothers.

The debate was chaired by Christophe Blanchet, vice president of the National Assembly, who presided over the sitting and coordinated the speaking time of all groups. The driving force behind the text was Christian Baptiste, Socialist affiliated deputy for Guadeloupe and rapporteur for the Law Committee, who authored the resolution, presented the statistical scale of incest (160,000 child victims per year, 77% within the family) and framed the commission as a way to expose systemic judicial failures and protect “protective parents,” especially mothers.

Around him, a cross party line up of speakers structured the political consensus: Florence Herouin Lautey (Socialists) traced the long cultural taboo around incest and denounced the tiny share of aggressors who are ever convicted; Arnaud Bonnet (Ecologists), visibly in tears, called on the nation “to really protect these children” and highlighted the criminalization of protective mothers; Éric Martineau (Democrats) and Michel Criaud (Horizons) backed the inquiry as a rigorous, non populist audit of judicial practice; Nicole Sanquer (LIOT) insisted on the “feeling of injustice” caused by non prosecution and contradictory civil decisions;

Karine Lebon (GDR) described incest as a mass crime, not a private matter; Eric Michoux and Sophie Blanc (Rassemblement National) underlined both the psychological devastation for children and the need to place them at the Centre of the justice system; while other deputies such as Perrine Goulet, Sandrine Josso, Maud Petit, Andrea Taurinya, Gabrielle Cathala, Justine Gruet and Nicole Sanquer contributed on children’s rights, resources and patriarchal bias, helping to forge the unanimous 195 to 0 vote that created the commission of inquiry.

The National Assembly’s unanimous decision to create an inquiry commission on parental incest and “protective parents” marks a rare moment of cross party unity around one of the darkest blind spots of French justice. As a field reporter covering the vote inside a Palais Bourbon labyrinth half blocked by renovation works, I owe a special thanks to the Assembly staff who patiently guided me through this obstacle course so I could attend a debate many deputies described as a moral imperative.

UNANIMOUS VOTE ON A “BLIND SPOT” OF JUSTICE

At the initiative of Christian Baptiste, Socialist affiliated deputy from Guadeloupe and rapporteur for the Law Committee, MPs voted on 28 January to set up a commission of inquiry into “the judicial treatment of parental incestuous sexual violence committed against children and the situation of protective parents, in particular protective mothers.” The resolution had already been co signed by more than 140 deputies from almost all groups, and was ultimately adopted without a single vote against. Baptiste framed the objective in stark terms: stopping sexual crimes against children must become “the absolute priority” of the national representation, he argued, recalling that an estimated 160,000 children are victims of rape or sexual assault each year in France and that roughly 77% of these attacks occur within the family

At the initiative of Christian Baptiste, Socialist affiliated deputy from Guadeloupe and rapporteur for the Law Committee, MPs voted on 28 January to set up a commission of inquiry into “the judicial treatment of parental incestuous sexual violence committed against children and the situation of protective parents, in particular protective mothers.” The resolution had already been co signed by more than 140 deputies from almost all groups, and was ultimately adopted without a single vote against. Baptiste framed the objective in stark terms: stopping sexual crimes against children must become “the absolute priority” of the national representation, he argued, recalling that an estimated 160,000 children are victims of rape or sexual assault each year in France and that roughly 77% of these attacks occur within the family

“THE PRIORITY OF THE NATION”: CHRISTIAN BAPTISTE’S ALARM

In a dense and at times harrowing speech, Christian Baptiste described parental incest as an “angle mort” of policy and law, tolerated by institutional fragmentation and denial. He illustrated his point with the case of a four year old girl handed over every Wednesday at 4:30 p.m. at a supervised contact point to a father suspected of sexual abuse, despite medical certificates noting repeated vulvitis and a perforated hymen, school and medical reports, child drawings and even paedophile files found on the father’s computer. For Baptiste, the system “organizes” situations where a man already banned from approaching minors may nonetheless keep his visitation rights to his own child, while the mother who refuses to comply risks prosecution for non presentation of a child. He denounced the presumption that fathers tell the truth while mothers are suspected of manipulation, insisting that the commission must examine how criminal, family and child protection judges fail to coordinate and why so many cases are closed without further action despite serious evidence.

In a dense and at times harrowing speech, Christian Baptiste described parental incest as an “angle mort” of policy and law, tolerated by institutional fragmentation and denial. He illustrated his point with the case of a four year old girl handed over every Wednesday at 4:30 p.m. at a supervised contact point to a father suspected of sexual abuse, despite medical certificates noting repeated vulvitis and a perforated hymen, school and medical reports, child drawings and even paedophile files found on the father’s computer. For Baptiste, the system “organizes” situations where a man already banned from approaching minors may nonetheless keep his visitation rights to his own child, while the mother who refuses to comply risks prosecution for non presentation of a child. He denounced the presumption that fathers tell the truth while mothers are suspected of manipulation, insisting that the commission must examine how criminal, family and child protection judges fail to coordinate and why so many cases are closed without further action despite serious evidence.

CHILD PROTECTION FAILURES AND HISTORIC TABOOS

From the Socialist benches, Florence Herouin Lautey placed the debate in a longer history of social denial, recalling how early public testimonies such as those of Eva Thomas in the 1980s or writer Christine Angot in the 1990s were met with mockery and hostility rather than support. She stressed that, despite the work of the independent Ciivise commission, incest is still not treated as a specific crime in the Penal Code, and that cousins remain excluded from the legal definition of incestuous violence even though they account for a significant share of aggressors. Citing estimates of more than seven million adults who have suffered incest and 130,000 children victimized each year by a family member, Herouin Lautey argued that only around 1% of offending parents are convicted, and that protective parents are sometimes criminalized instead. For her, the inquiry must expose systemic dysfunctions that leave victims without justice and reduce the child’s word to something “suspected, minimized or disqualified.”

From the Socialist benches, Florence Herouin Lautey placed the debate in a longer history of social denial, recalling how early public testimonies such as those of Eva Thomas in the 1980s or writer Christine Angot in the 1990s were met with mockery and hostility rather than support. She stressed that, despite the work of the independent Ciivise commission, incest is still not treated as a specific crime in the Penal Code, and that cousins remain excluded from the legal definition of incestuous violence even though they account for a significant share of aggressors. Citing estimates of more than seven million adults who have suffered incest and 130,000 children victimized each year by a family member, Herouin Lautey argued that only around 1% of offending parents are convicted, and that protective parents are sometimes criminalized instead. For her, the inquiry must expose systemic dysfunctions that leave victims without justice and reduce the child’s word to something “suspected, minimized or disqualified.”

EMOTION ON THE ECOLOGIST BENCHES

One of the most striking moments came from Arnaud Bonnet, an Ecologist deputy and member of the parliamentary delegation for children’s rights. Speaking in a trembling voice and briefly breaking down in tears, he urged colleagues “to really protect these children,” reminding them that every three minutes a child in France falls victim to sexual violence, with nearly 80% of these acts committed within the family. Bonnet described a “second violence” suffered by protective parents most often mothers who are prosecuted for non presentation of a child after refusing to send them to a suspected abuser, sometimes with tragic outcomes including child suicides. He spoke of a “structural” problem documented by the Ciivise, the High Council for Equality and even the UN Committee against Torture, which in 2025 criticized France for “institutional torture” inflicted on children and protective mothers. The new commission, he insisted, must not be seen as an attack on judges but as a constitutional tool to understand how civil and criminal decisions can contradict each other and endanger children.

One of the most striking moments came from Arnaud Bonnet, an Ecologist deputy and member of the parliamentary delegation for children’s rights. Speaking in a trembling voice and briefly breaking down in tears, he urged colleagues “to really protect these children,” reminding them that every three minutes a child in France falls victim to sexual violence, with nearly 80% of these acts committed within the family. Bonnet described a “second violence” suffered by protective parents most often mothers who are prosecuted for non presentation of a child after refusing to send them to a suspected abuser, sometimes with tragic outcomes including child suicides. He spoke of a “structural” problem documented by the Ciivise, the High Council for Equality and even the UN Committee against Torture, which in 2025 criticized France for “institutional torture” inflicted on children and protective mothers. The new commission, he insisted, must not be seen as an attack on judges but as a constitutional tool to understand how civil and criminal decisions can contradict each other and endanger children.

CENTRIST AND HORIZONS DEPUTIES BACK A “NECESSARY AUDIT”

From the centrist group Les Democrates, Eric Martineau confirmed his group would support the resolution “with responsibility and seriousness,” warning against both judicial populism and complacency. He pointed to the gap between some 14,100 people implicated in cases each year and about 4,300 convictions, as well as the fact that only 15% of incestuous sexual violence ends up legally qualified as rape, calling this an “abyssal discrepancy” the commission must clarify. Michel Criaud, speaking for Horizons and Independents, also endorsed the inquiry, stressing that it targets a public policy justice rather than individual cases, and that no ongoing proceedings are being interfered with. For both deputies, a trans-partisan parliamentary investigation is now the only way to craft better legislative tools against a “terrifying” phenomenon in which three quarters of child sexual violence is incestuous.

From the centrist group Les Democrates, Eric Martineau confirmed his group would support the resolution “with responsibility and seriousness,” warning against both judicial populism and complacency. He pointed to the gap between some 14,100 people implicated in cases each year and about 4,300 convictions, as well as the fact that only 15% of incestuous sexual violence ends up legally qualified as rape, calling this an “abyssal discrepancy” the commission must clarify. Michel Criaud, speaking for Horizons and Independents, also endorsed the inquiry, stressing that it targets a public policy justice rather than individual cases, and that no ongoing proceedings are being interfered with. For both deputies, a trans-partisan parliamentary investigation is now the only way to craft better legislative tools against a “terrifying” phenomenon in which three quarters of child sexual violence is incestuous.

VOICES FROM THE TERRITORIES AND OVERSEAS FRANCE

Nicole Sanquer, for the LIOT group, insisted that state inaction in the face of intra familial abuse constitutes a failure, especially when the family home where children should be safest becomes the primary site of violence. She underlined that many complaints are still closed without further action, leaving children unprotected and mothers punished for trying to shield them, and called the inquiry an “absolute necessity” to map every stage of the procedure from complaint to final judgment. From La Réunion, Karine Lebon of the GDR group painted a vivid picture of children abused “in a chic flat in the 7th arrondissement” or in overcrowded homes in the overseas territories, arguing that the numbers :160,000 children, 77% within the family, 95% of aggressors male are too clear for incest to be considered a marginal or private issue. She cited the report “Un crime d’Etat” and UN recommendations as proof that institutional delays and contradictory decisions amount to a “second trauma” telling children: “you hurt, but we don’t see you; you hurt, but we don’t believe you.”

Nicole Sanquer, for the LIOT group, insisted that state inaction in the face of intra familial abuse constitutes a failure, especially when the family home where children should be safest becomes the primary site of violence. She underlined that many complaints are still closed without further action, leaving children unprotected and mothers punished for trying to shield them, and called the inquiry an “absolute necessity” to map every stage of the procedure from complaint to final judgment. From La Réunion, Karine Lebon of the GDR group painted a vivid picture of children abused “in a chic flat in the 7th arrondissement” or in overcrowded homes in the overseas territories, arguing that the numbers :160,000 children, 77% within the family, 95% of aggressors male are too clear for incest to be considered a marginal or private issue. She cited the report “Un crime d’Etat” and UN recommendations as proof that institutional delays and contradictory decisions amount to a “second trauma” telling children: “you hurt, but we don’t see you; you hurt, but we don’t believe you.”

FAR RIGHT AND RIGHT WING SUPPORT

Even the far right Rassemblement national lined up behind the commission. RN deputy Eric Michoux noted that self reported victims of incest in France had risen from two to almost seven million between 2009 and 2020, reflecting both the scale of the phenomenon and a slow lifting of the taboo. His colleague Sophie Blanc stressed the long term psychological impact of parental incest, pointing to clinical work on trauma and dissociation to argue that children’s fragmented accounts are symptoms of abuse, not proof of lying. For Blanc, the key issue is the paradox of parallel procedures: lengthy or incomplete criminal investigations, decisions to maintain contact or even overnight stays with a suspected parent, and the criminalization of mothers who refuse to comply. On the traditional right, Philippe Gosselin for Droite Republicaine presented the inquiry as a legitimate exercise of parliamentary oversight that does not undermine judicial independence but responds to alerts from the UN and independent French bodies; his group, he confirmed, would “join the rapporteur with conviction.”

Even the far right Rassemblement national lined up behind the commission. RN deputy Eric Michoux noted that self reported victims of incest in France had risen from two to almost seven million between 2009 and 2020, reflecting both the scale of the phenomenon and a slow lifting of the taboo. His colleague Sophie Blanc stressed the long term psychological impact of parental incest, pointing to clinical work on trauma and dissociation to argue that children’s fragmented accounts are symptoms of abuse, not proof of lying. For Blanc, the key issue is the paradox of parallel procedures: lengthy or incomplete criminal investigations, decisions to maintain contact or even overnight stays with a suspected parent, and the criminalization of mothers who refuse to comply. On the traditional right, Philippe Gosselin for Droite Republicaine presented the inquiry as a legitimate exercise of parliamentary oversight that does not undermine judicial independence but responds to alerts from the UN and independent French bodies; his group, he confirmed, would “join the rapporteur with conviction.”

QUESTIONS OF MEANS AND PATRIARCHAL CULTURE

Several left wing deputies, including Andrea Taurinya and Gabrielle Cathala, tried to widen the commission’s scope to explicitly address budgetary resources and patriarchal structures underpinning incest and the persecution of protective mothers. They denounced the persistence of pseudo concepts such as “parental alienation syndrome,” promoted by masculinist networks despite its removal from international classifications, and warned that without adequate funding for justice, child protection services and specialist interview rooms, even the best legal reforms would remain on paper. While the rapporteur resisted making budget an explicit axis of the inquiry arguing time was limited and the core mandate must remain focused he acknowledged that questions of staff and funding would inevitably surface in hearings and recommendations.

Several left wing deputies, including Andrea Taurinya and Gabrielle Cathala, tried to widen the commission’s scope to explicitly address budgetary resources and patriarchal structures underpinning incest and the persecution of protective mothers. They denounced the persistence of pseudo concepts such as “parental alienation syndrome,” promoted by masculinist networks despite its removal from international classifications, and warned that without adequate funding for justice, child protection services and specialist interview rooms, even the best legal reforms would remain on paper. While the rapporteur resisted making budget an explicit axis of the inquiry arguing time was limited and the core mandate must remain focused he acknowledged that questions of staff and funding would inevitably surface in hearings and recommendations.

CONCLUSION: A RARE MOMENT OF UNITY AROUND CHILDREN’S RIGHTS

In the end, the resolution to create the commission of inquiry was adopted with 195 votes in favour and none against, formalizing an unanimity rarely seen in the current fragmented Assembly. The debate itself was marked by applause across benches, explicit thanks to survivor associations and experts, and the visible emotion of deputies like Arnaud Bonnet, whose tears underscored the human weight behind statistics that count 160,000 child victims a year “160,000 too many,” as one speaker put it. Lawmakers from all political families converged on one point: the current system too often fails to protect children from parental abusers and punishes those who try to shield them, in part because of slow procedures, lack of coordination and deep seated cultural biases. The new commission now carries the burden of turning that consensus into concrete recommendations, with the declared ambition of finally putting the “best interests of the child” at the centre of French justice and of ending a form of institutional blindness that survivors and protective parents have been denouncing for years.

In the end, the resolution to create the commission of inquiry was adopted with 195 votes in favour and none against, formalizing an unanimity rarely seen in the current fragmented Assembly. The debate itself was marked by applause across benches, explicit thanks to survivor associations and experts, and the visible emotion of deputies like Arnaud Bonnet, whose tears underscored the human weight behind statistics that count 160,000 child victims a year “160,000 too many,” as one speaker put it. Lawmakers from all political families converged on one point: the current system too often fails to protect children from parental abusers and punishes those who try to shield them, in part because of slow procedures, lack of coordination and deep seated cultural biases. The new commission now carries the burden of turning that consensus into concrete recommendations, with the declared ambition of finally putting the “best interests of the child” at the centre of French justice and of ending a form of institutional blindness that survivors and protective parents have been denouncing for years.

Liability for this article lies with the author, who also holds the copyright. Editorial content from USPA may be quoted on other websites as long as the quote comprises no more than 5% of the entire text, is marked as such and the source is named (via hyperlink).